Notes on the Synthesis of Form is a book written by architect and design theorist Christopher Alexander and originally published in 1964. It has become highly influential in a number of fields: mainly architecture, urban planning and computer science slash software engineering, for its highly original and powerful logical, even mathematical approach to design.

I read the book recently and really enjoyed it. I felt like it gives words and a solid theory to a deeply intuitive idea: that designing or building something requires a very detailed and studied understanding of what you are designing or building it for. This simple idea almost sounds like a tautology, but it is remarkable how often it is abused, ignored or degraded. Below are a few notes and thoughts I had while reading the book, which I would really recommend to anyone interested in designing and building systems of any kind.

Part I

The first part of the text is full of analogies and metaphors, which at the beginning try to capture the highly intuitive notion of “fit” and “misfit” of forms of all kinds. The very first metaphor is of iron filings in a magnetic field: the process which dictates the form that the filings jump into when the field is switched on is not visible, but certainly exists. The same is true, Alexander reckons, for many other kinds of invisible forces: cultural, environmental, physical, human, which inform and ultimately shape the form of all manner of things in the world.

The central focus of this part is on the difference between what Alexander calls “selfconscious” and “unselfconscious” cultures. He is hesitant to give a more loaded meaning, but it is clear from the examples that he gives that he is talking about pre- and post-enlightenment thinking. Individualism and skepticism of tradition are very problematic for the kind of generational form-making processes, like those which design the certain dwellings that tribes around the world build depending on their environment. These processes happen through the accumulation of small “corrections of misfits” – fixing things when they are broken – across generations, with no single person acting as anything more than an agent in some natural process of convergence to an equilibrium. When theories and opinions emerge, these cause fatal friction to these natural form-making processes. He argues that selfconscious cultures have a tendency to try to break large design problems down into subproblems based on contrived divisions, ultimately sourced from our ambiguous and culturally loaded languages, which do not reflect the subdivisions that would emerge in the “natural” process (all feels a bit inspired by Plato’s Cave).

Detailed analysis of the problem of designing urban family houses, for instance, has shown that the usually accepted functional categories like acoustics, circulation, and accommodation are inappropriate for this problem. Similarly, the principle of the “neighborhood,” one of the old chestnuts of city-planning theory, has been shown to be an inadequate mental component of the residential planning problem. (p66)

Part II

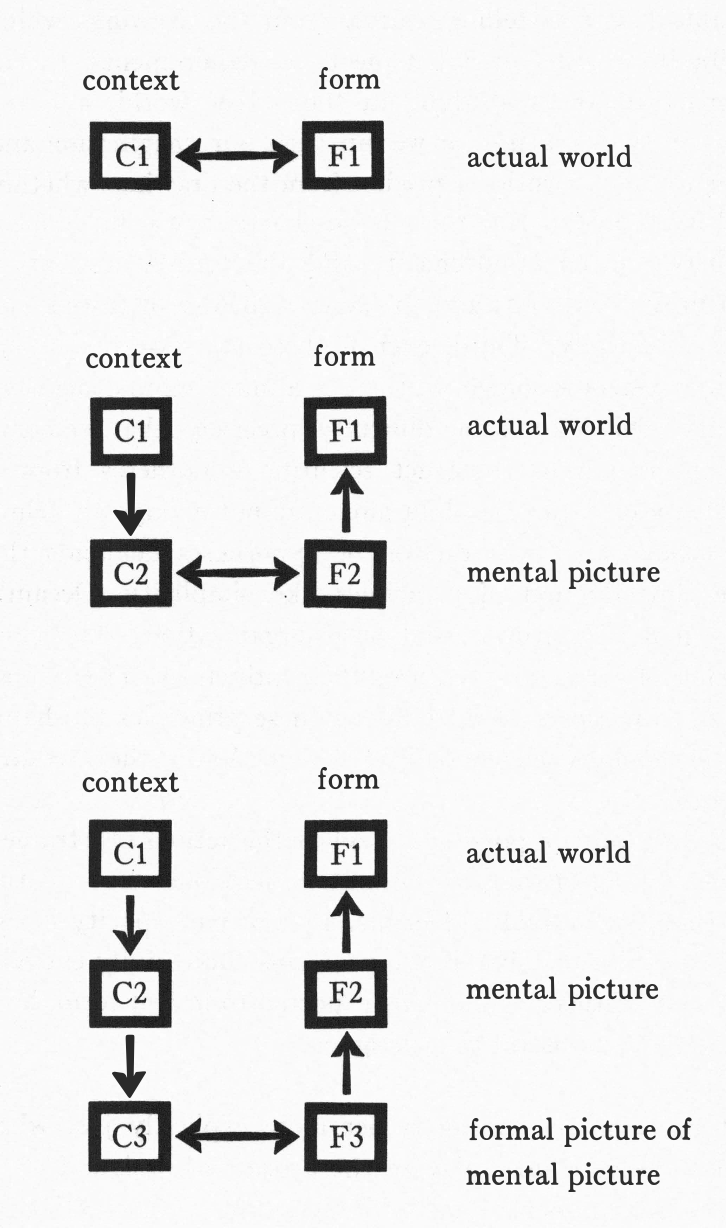

The second part of the book presents a framework for studying and decomposing design problems which Alexander suggests is free of this bias. He proposes a new method, an additional abstraction on top of the existing “selfconscious” method, which “eradicates its bias and retains only its abstract structural features; this second picture may then be examined according to precisely defined operations, in a way not subject to the bias of language and experience” (p77).

He does this by venturing into pure mathematics, specifically set theory, graph theory and probability theory, something which you do not see in the architectural literature very often I imagine. He imagines enumerating all the “misfit” variables which represent “individual conditions which must be met at the form-context boundary”, \(x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_m\) – this is the set \(M\). He then associates with \(M\) a second set \(L\) – a set of non-directed, signed, weighted edges between elements of \(M\). The weights are negative if they indicate conflict, and positive if they indicate concurrence, and may also be weighted to indicate strength of interaction. This is just a line graph, referred to in Alexander’s day as a “linear graph”.

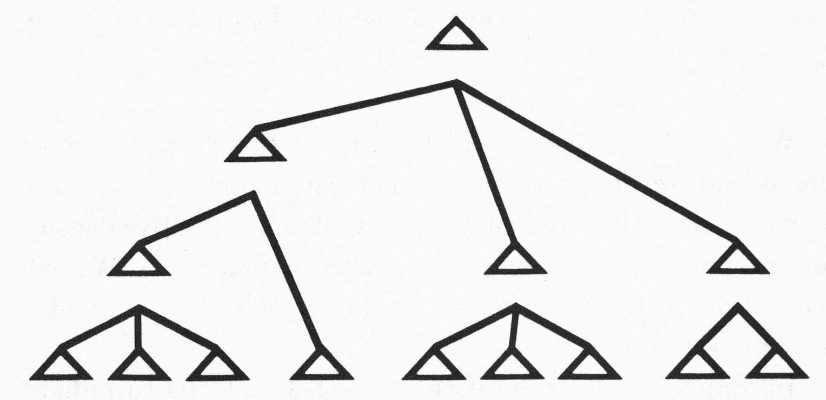

He then goes on to define “decompositions” of the set \(M\) into hierarchical tree-like structures, and the goal of the “program”: to find some clustering of nodes of this graph which most naturally seems to fit the underlying link structure \(L\).

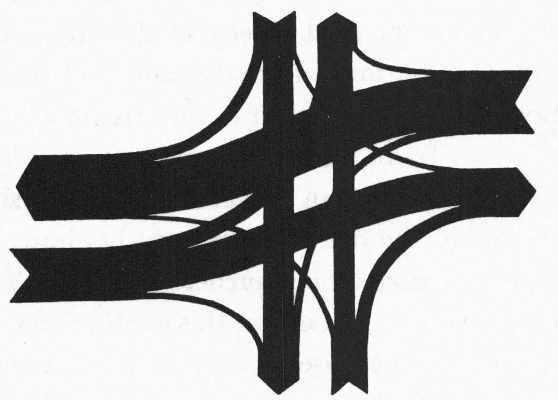

At this stage it felt like we were about to solve some well-known NP-hard graph theory problem, but instead Alexander takes a detour into the theory of diagrams, defining a “constructive” diagram to be something that is both a form diagram and a requirement diagram. To explain this, he gives the genius example of how to specify the requirement that traffic can flow without congestion at a junction between two streets. You could provide a table of numbers with the relative frequency of each of the different paths at the junction, or you could compose the diagram below which presents the information, but also very strongly hints at its implications on the solution’s form. He claims that constructive diagrams of this sort are the output of this program.

Some of the “misfit” variables are easy to deal with because they exist on some measurable, numeric scale that allows for the establishment of a “performance standard”. For example we can establish fairly well that the minimum width for a highway lane is 11 feet because of what we know about modern cars and motorway speeds. This means the misfit variable corresponding to “is this motorway safe from between-lane accidents” is simple. But the real interesting parts of design, and of life of course, lie in those things which do not have such a numerical interpretation.

Some typical examples are “boredom in an exhibition,” “comfort for a kettle handle,” “security for a fastener or a lock,” “human warmth in a living room,” “lack of variety in a park.” (p98)

Here comes the blow to my mathematical fantasy: “a design problem is not an optimization problem”. He means this in the sense that we lose optimality on many of these “richer” “performance standard” axes by restricting their misfit variable to be binary. And now we come to the three central questions:

- How can we get an exhaustive set of variables \(M\) for a given problem; in other words, how can we be sure we haven’t left out some important issue?

- How do we know that all the variables we include in the list \(M\) are relevant to the problem?

- For any specific variable, how do we decide at what point misfit occurs; or if it is a continuous variable, how do we know what value to set as a performance standard? In other words, how do we recognize the condition so far described as misfit?

As to the first one, as you would expect, the advice is to give up. \(M\) can only really ever be a “temporary catalogue of those errors which seem to need correction”.

He then defines the “form domain” \(D\) as “the totality of possible forms within the cognitive reach of the designer given the context”, and for each misfit variable \(x_i\) defines \(p(x_i=1)\) to be the proportion of forms in \(D\) which are a misfit for \(x_i\). In this way we can define correlation coefficients \(c_{ij}\) between pairs \(x_i,x_j\) of misfits in the usual statistical way.

- If \(c_{ij}\) is markedly less than \(0\), \(x_i\) and \(x_j\) conflict; like “The kettle’s being too small” and “The kettle’s occupying too much space.” When we look for a form which avoids \(x_i\), we weaken our chances of avoiding the other, \(x_j\).

- If \(c_{ij}\) is markedly greater than 0, \(x_i\) and \(x_j\) concur; like “the kettle’s not being able to withstand the temperature of boiling water” and “the kettle’s being liable to corrode in steamy kitchens.” When we look for materials which avoid one of these difficulties, we improve our chances of avoiding the other.

- If \(c_{ij}\) is not far from 0, \(x_i\) and \(x_j\) exhibit no noticeable interaction of either type.

We can use these \(c_{ij}\) as the weights of links in our graph. He notes that this gives a way to estimate these weights empirically, by measuring the existing forms. But these of course may (almost certainly will) provide a biased sample of \(D\). Instead he suggests searching for causal connections between variables. It really is wild to think this book was written in 1964. He puts the onus on the designer now:

We shall say that two variables interact if and only if the designer can find some reason (or conceptual model) which makes sense to him and tells him why they should do so. […] \(L\), like \(M\), is a picture of the way the designer sees the problem, not an objective description of the problem itself”. (p109)

He wants to search the graph for dense subclusters, where he believes can be found “particularly strong identifiable physical aspect[s] of the problem”. (p122) I think this sounds a lot like the min-cut problem.

Into the maths now: for a partition \(\pi\) of a set \(S\) we define a “measure of information transfer” \(R(\pi)\). We then use this to partition \(M\), and then successively partition the subsets in the partition, until we obtain a full tree of sets where each leaf is a singleton. He claims that the output of this process, if your set \(M\) and data \(L\) is rich enough, is a constructive diagram that can provide insights about the desired form.

Appendices

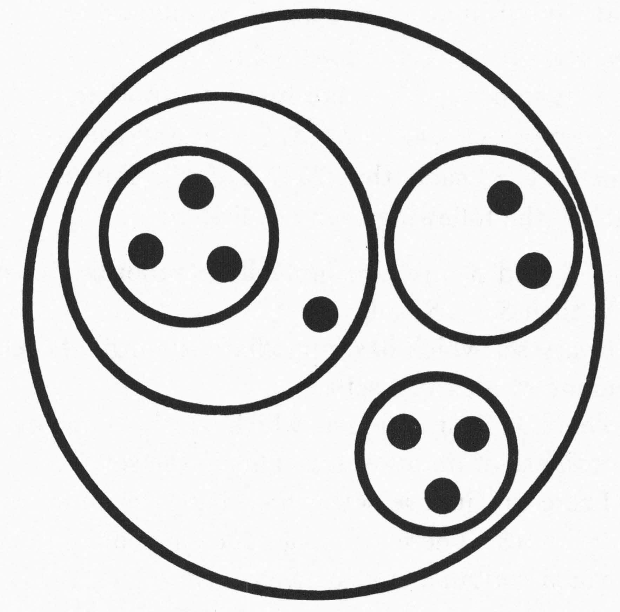

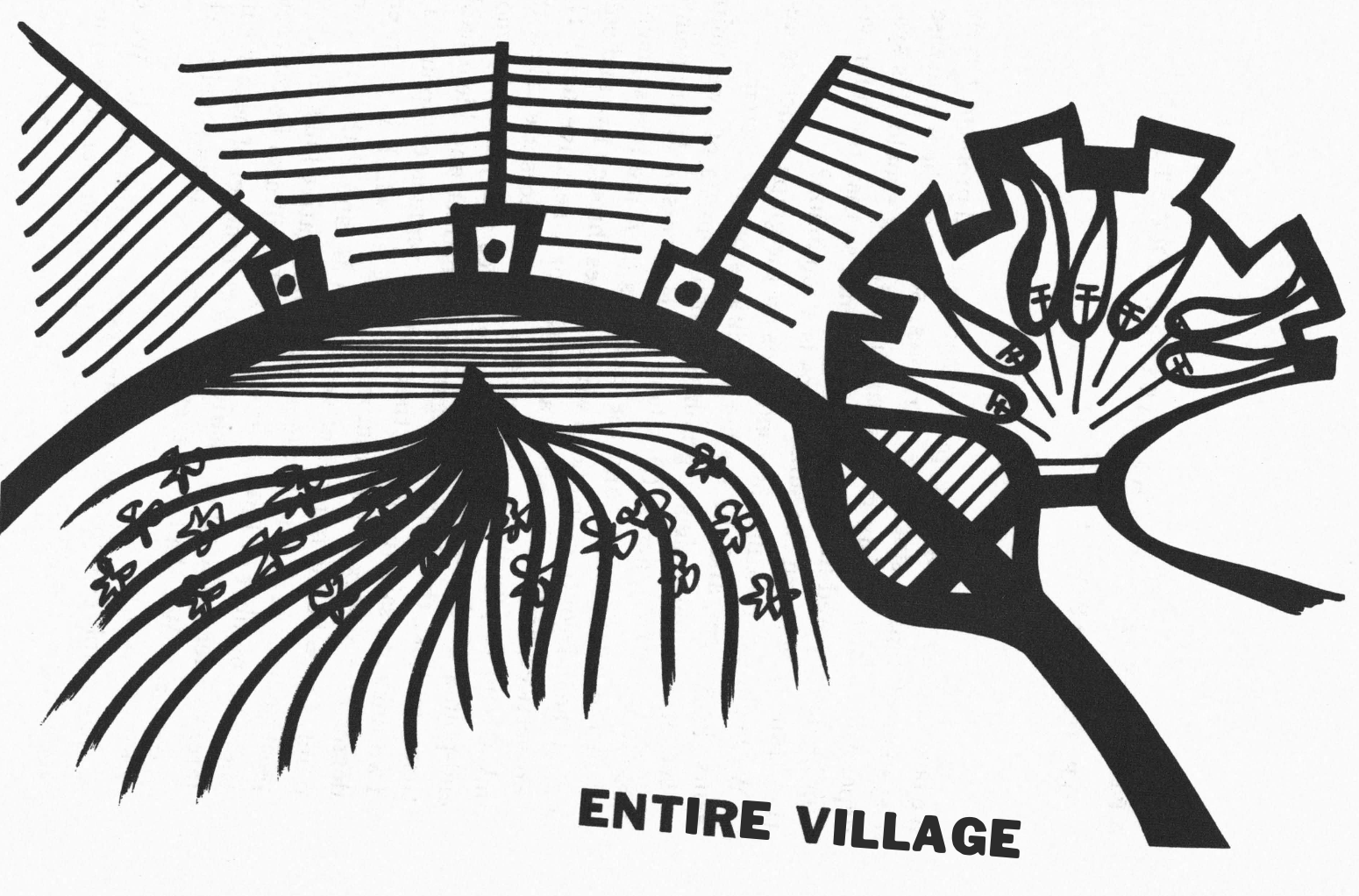

The next part of the text is a 36-page case study, using the methods derived in the book to determine the form of a rural Indian village, which produces the following constructive diagram:

After that, the maths: Alexander uses probability theory and graph theory to derive a closed-form equation for his \(R(\pi)\) function for information transfer between subsets of a partition of the nodes a line graph. I found this fascinating, but it might be over some peoples’ heads; I think if you’re interested the best thing to do is to read the Appendix 2. I will add the equation for good measure:

\[R(\pi)=\frac{\frac12 m(m-1)\sum_{\pi}v_{ij} - \ell \sum_{\pi}s_{\alpha}s_{\beta}}{\Bigl[\Bigl(\sum_{\pi}s_{\alpha}s_{\beta}\Bigr)\Bigl(\frac12m(m-1)\Bigr)-\sum_{\pi}s_{\alpha}s_{\beta}\Bigr]^{\frac12}}\]So overall a great book, a really good example of how abstraction can help provide clarify when properly considered. Lots of very big ideas in here about things that just seem so natural that it’s weird no one has thought of them before. Alongside the theoretical purity and originality of Alexander’s proposed method, I really enjoyed thinking about those “unselfconscious” processes, the kinds of things which are becoming rarer and rarer in the world today. The “enshittification” of forms of all kinds throughout the world can maybe be thought of as a loss of connection with these more primitive form-making processes.